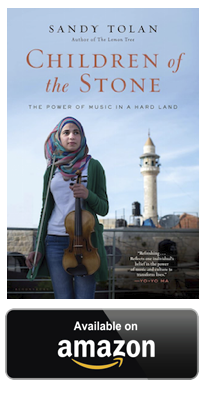

To promote the release of Sandy Tolan’s latest book, Children of the Stone, Ramallah Café presents Grace Notes, short excerpts curated by the author himself. The book, about one Palestinian’s dream to build a music school in the middle of a military occupation, is out today. Children of the Stone is already receiving wide praise from historians, early reviewers, and the famed musician Yo-Yo Ma. More here. In the coming weeks, you’ll even be able to read excerpts ahead of scheduled release–just by sharing with friends.

————

For Ramzi, at first, it was like a game. Soldiers came; he threw stones at them; they chased him; he escaped. His favorite place to begin the ritual was a yellow stucco wall at a house on the corner of Al Amari’s main road, about one hundred fifty meters from the four-story stone building and the entrance to the camp. Across the road he could see the white plaster minaret of the camp mosque, where, five times a day, the muezzin made the musical call to prayer. During the chaos of the occupation and the resulting absence of local government, the mosque had become a focal point of community life and a trusted civic institution for the exchange of vital information in the camp. Frequently Al Amari’s news was announced over the loudspeaker on the minaret. Next to the mosque stood Kareem’s grocery, with the overstuffed shelves where the brothers got their half-shekel chocolate biscuits.

On a cold morning in early 1988, the older shabab were smashing big rocks and curbstones into smaller pieces, good for throwing. Ramzi watched them wrap their faces in checkered keffiyehs, to guard their identities from the military surveillance crews and the informants, and to protect themselves from teargas. Others deployed fresh-cut onions to dull the effects of the gas.

Ramzi and the other young boys began crumpling newspapers and stuffing them into tires, the better to get them smoking. From his pocket Ramzi pulled out the slingshot he had made from the laces and tongue of an old shoe. He preferred this for long-distance targets. The boys rotated their arms like baseball pitchers warming up in the bullpen. This way, they wouldn’t get cramps.

Someone lit a match. From the blazing tires, twisting black columns rose above the camp, signaling the start of another day of battle. At the camp entrance, soldiers formed an unbroken line. Often they kept their distance, firing teargas canisters, rubber-coated metal bullets, and, occasionally, live ammunition to disperse the crowds. Today, however, the line began to move forward.

Ramzi wrapped his right hand around a jagged piece of curbstone. He glanced behind him to the long row of cement-block homes, checking his escape route. On the rooftops, laundry flapped from metal wires suspended between posts. Crooked TV antennas poked toward the sky

He wore blue jeans and tennis shoes; his red jacket with the faux-sheepskin collar was flying open. In his left hand Ramzi held a rock nearly half the size of his head. His raised right arm was drawn behind him, his hand clutching the piece of curbstone. Ramzi’s eyes conveyed a mixture of anger, fear, and resolve. His arched eyebrows seemed to say, We are here. His left foot was planted, and he was stepping forward with his right. In one more second, the stone would fly.

In that instant, a photojournalist snapped a picture. It captured a lone boy—one of thousands of the atfal al hijara, or children of the stones—confronting an unseen army.

The stone flew and the chase was on. Ramzi turned and ran hard around the corner, past the stucco wall, down the alley toward the bakery. “Stop!,” a voice called in accented Arabic just behind him. Elated and terrified, Ramzi zigzagged through the camp, darting left, doubling back through a darkened passage, bursting into a neighbor’s house, climbing through an upstairs window, and racing along the rooftops.

Still, he hadn’t shaken his pursuer, who ran along below, pointing and shouting.

Ramzi felt his sneakers grabbing the dimples of the tin roof; he saw his limbs pumping in a perfect rhythm with his panting breath. In times like these, in full flight from the soldiers, a strange sense of calm often settled over him. There wasn’t time to put words to a prayer, but he put out the energy of a fragmented offering: God, I love you. I need you. I need to be alive. There was nothing more in the world that could help him; once, a bullet whizzed past, and he understood his life in terms of centimeters. Oddly, in these moments, Ramzi felt protected: buoyed, lifted, and cared for as he ran and ran, sprinting from rooftop to rooftop, leaping toward an imagined freedom.

Click here to read the next Grace Notes…

The latest book from acclaimed journalist Sandy Tolan, Children of the Stone chronicles the journey of Ramzi Hussein Aburedwan—from stone thrower to music student to school founder—and shows how through his love of music he created something lasting and beautiful in a land torn by violence and war.

Tags: children of the stone, Israel, music, occupation, palestine, sandy tolan