These five maps tell their own history of the Israeli-Palestinian Struggle. From “Children of the Stone” (Bloomsbury, 2015).

A popular history of the birth of Israel — what we might call the Leon Uris “Exodus” history — describes a nation rising out of the ashes of the Holocaust, as hundreds of thousands of Jewish survivors joined fellow Zionists to reclaim the promised land from its empty, barren past. “Today the Jewish people are again at a period of Genesis,” Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion declared. “A waste land must be made fertile and the exiles gathered in.” Many of the emigrants had been inspired by the Zionist slogan, “People without land go to a land without people.”

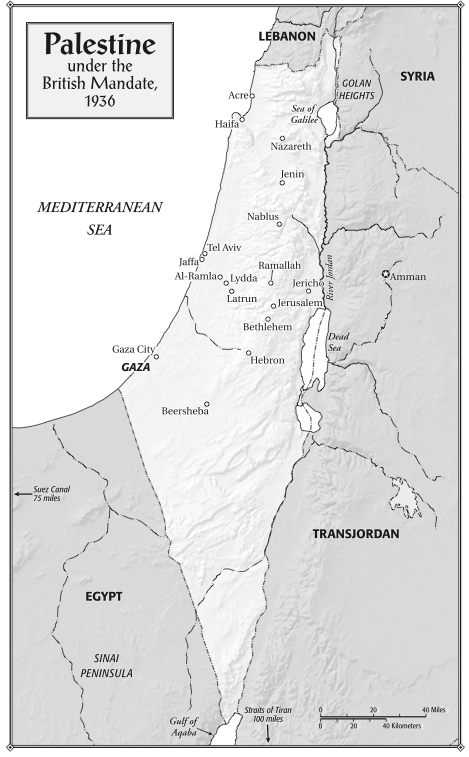

Of course, there were people already there, ignored by Uris’s powerful but terribly incomplete narrative. By 1936, about a million mostly rural Palestinian Arabs lived in historic Palestine, annually harvesting hundreds of thousands of tons of barley, wheat, tomatoes, cucumbers, grapes, figs, olives, and citrus. And their history — indeed the history of the Palestinian-Israeli tragedy — can be told in part by a series of maps (from Children of the Stone).

MAP 1, from 1936, shows the whole of Palestine, undivided, under a single jurisdiction known as the British Mandate. Two decades earlier, in the Balfour Declaration, the British had promised a homeland to the Jews in Palestine; the Arabs strongly opposed it. In 1922, the Jewish population stood at 84,000, or about 11 percent of the population — up from about 4 percent in the mid-19th Century. The steady flow, spurred by European Zionism, became a flood after Hitler came to power in 1933; three years later, the Jewish population stood at 352,000 — a quadrupling in just 14 years. Tensions between Arabs and Jews intensified over Jewish emigration, and in 1936 the Arabs of Palestine launched a revolt. The Palestinian Arab population wanted an end to the immigration, and for the land to stay intact, undivided, as an independent state after British rule.

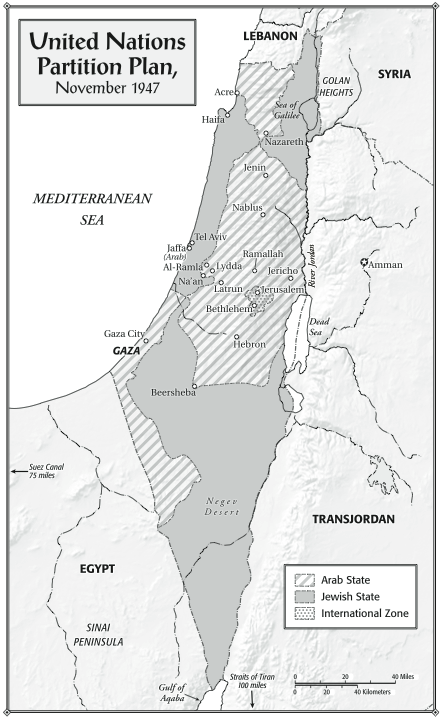

MAP 2, from 1947, shows the proposed partition plan for Arab and Jewish states — the result of a 33-13 vote in the United Nations. Jews, with about a third of the population, and owning 7 percent of the land, would receive 55 percent of historic Palestine; the rest, minus a tiny portion for an internationally-administered Jerusalem, would form the Arab state. One Jewish scholar saw the vote as a “gesture of repentance for the Holocaust.” Palestinian Arabs objected. In the words of Harvard Palestinian scholar Walid Khalidi: “The Palestinians failed to see why they should be made to pay for the Holocaust…why was it fair for almost half of the Palestinian population — the indigenous majority on its ancestral soil — to be converted overnight into a minority under alien rule in the envisaged Jewish state according to partition.” Palestinian Arabs pledged to fight the establishment of the new Jewish state.

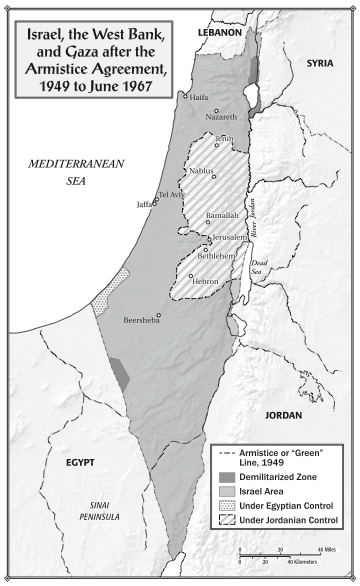

MAP 3 below shows the results of the 1948 war, in which forces from several Arab states were defeated by Israel’s army. Some 750,000 Palestinians fled or were driven out of their homes in what became Israel, in a collective trauma known to every Palestinian as the Nakba, or Catastrophe, David Ben-Gurion depicted the victory, known to Israelis as the War of Independence, in miraculous terms: “700,000 Jews against 27 million Arabs — one against 40.” The relevant number, however, was not the entire Arab population (most of whom lived far from Palestine), but troop strength. In fact the numbers of forces on the ground were relatively equal, and by the end of the war, Israel had superior weaponry, much of operated by battle-hardened veterans of World War II. In any event, the result of the war was that Israel’s portion of historic Palestine, compared to the U.N. partition, had increased to 78 percent; Palestinians, in the West Bank and Gaza, now had 22 percent, which was administered by Jordan and Egypt respectively. This geographic reality remained until the Six Day War in June 1967. The refugees, meanwhile, were not allowed to come home, despite a U.N. resolution advocating for their return. Palestinians, led by Yassir Arafat, vowed to liberate Palestine, and various Palestinian factions launched periodic attacks against Israel.

Israel, the West Bank, and Gaza after the Armistice Agreement, 1949 to 1967. From “Children of the Stone” (Bloomsbury, 2015).

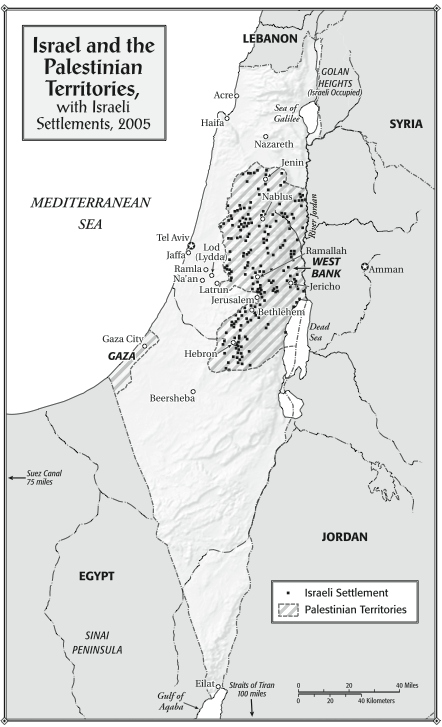

MAP 4 (below), from 2005, shows the entrenched results of Israel’s victory in the 1967 war: Jewish settlements dotting the West Bank. The settlement project began in earnest in the 1970s, spurred initially by Israel’s Labor Party leaders, including Shimon Peres, and afterward championed by the future Israeli prime minister, Ariel Sharon. Sharon had boasted to a British journalist (who happened to be the grandson of Winston Churchill) in 1973 that Israel would turn the West Bank into a “pastrami sandwich”: “We’ll insert a strip of Jewish settlement in between the Palestinians. And then another strip of Jewish settlement, right across the West Bank, so that in twenty-five years’ time, neither the United Nations, nor the United States, nobody, will be able to tear it apart.” Indeed Sharon, and Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu after him, essentially carried out the “pastrami sandwich” plan. In 1993, at the beginning of the Oslo “peace process,” 109,000 Jewish settlers resided on the West Bank, not including Jerusalem; today they number 380,000. East Jerusalem, once entirely Arab, and the would-be future capital of Palestine, is now ringed by hilltop Jewish settlements, almost entirely cut off from the rest of the West Bank. And a land corridor between the West Bank and Gaza, promised under Oslo, never came to be.

Israel and the Palestinian Territories, with Israeli Settlements, 2005. From “Children of the Stone” (Bloomsbury, 2015).

Finally, MAP 5 shows the reality of land control in the West Bank today. Under the Oslo regime, the territory was divided into three jurisdictions. Area A, quasi-sovereign control by the Palestinian Authority, makes up 18 percent of the West Bank. Area B, under joint Israeli-Palestinian control, accounts for 22 percent. The rest, 60 percent of the West Bank, is under full Israeli military control. The West Bank, in turn, makes up barely one fifth of historic Palestine. Thus Palestinians, whose national liberation movement once sought to reclaim all the land between the Mediterranean Sea and the River Jordan, now have partially autonomous control over 4 percent of it. Those semi-sovereign lands (Israeli can enter at any time by notifying Palestinian authorities) are scattered in islands in a sea of Israeli military control. Between them, hundreds of military checkpoints dot the West Bank, a territory slightly smaller than the state of Delaware.

Maps from “Children of the Stone,” by SANDY TOLAN. Purchase now or learn more here. Coming soon in the “Knife Intifada” CONTEXT series: East Jerusalem.