Read all of the excerpts from the first week of Grace Notes.

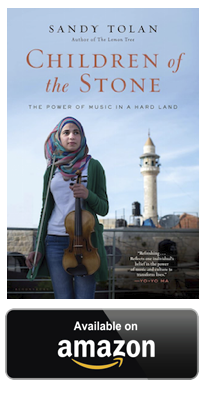

To promote the release of Sandy Tolan’s latest book, Children of the Stone, Ramallah Café presents Grace Notes, short excerpts curated by the author himself. The book, about one Palestinian’s dream to build a music school in the middle of a military occupation, was released on April 7. Children of the Stone is already receiving wide praise from historians, early reviewers, and the famed musician Yo-Yo Ma. More here.

————

Five young men stare through the windows of their bus, stalled at a military checkpoint known as Qalandia. Outside, an exhaust-choked border crossing divides Jerusalem from the West Bank city of Ramallah. Behind it stands a massive gray wall, seemingly impenetrable except by special permission. The men look out as drivers jockey for position, funneling into a single line before submitting for inspection. Vendors, mostly children, weave through the knots of vehicles, amid the plastic litter and chunks of broken concrete, selling kebab, tissue packets, pillows, bottles of water, and verses from the Qur’an.

Soldiers enter the bus, M-16s on their shoulders. A young woman inspects documents. She orders twenty people off the bus, including the five young men. They will not be allowed to cross the checkpoint in relative dignity, unlike the foreigners who remain on the air-conditioned coach. Instead, they walk through the heat into a trash-strewn terminal and pass down a long narrow corridor framed by silver bars. It looks like a cattle chute on a western American ranch. At the end the men push through two eight-foot-high turnstiles known as iron maidens. A stray cat straddles a wall above them. KEEP THE TERMINAL CLEAN, a sign instructs.

The men crowd with dozens of others into a small holding area in front of a third floor-to-ceiling turnstile. Every few minutes a red light turns green, a click sounds, and three or four more people pass through the iron maiden to place their possessions on a conveyor belt. They hold up their permits to a dull green bulletproof window and look through the smoky glass, waiting. On the other side, bored-looking soldiers glance up, inspect the documents, and, one by one, wave the permit-holders through.

All but the five young men. “You do not have proper permits,” they are told.

Denied the Holy City, the men click their way backward through the gates, along the metal chute, and into the maze of cars and vendors, uncertain what to do next. It is urgent that they reunite with the others on the bus, so they can all reach Jerusalem.

“Hey, boys,” calls an unshaven man sitting on a stool inside a crude metal shed. The man takes a drag of his cigarette. He glances at the glass tumbler in his hand and the dregs of his Turkish coffee. The young men look behind him, toward the twenty-five-foot-high wall. They approach. Two of them carry long felt bags; another holds a blue canvas case.

The unshaven man takes a last drag of his cigarette, flicks it in the dirt, and looks up. “Ya, shabab,” he says, exhaling a long column of smoke. He smiles. “You boys need to get to Jerusalem?”

“Yes,” says the oldest of the five young men. He appears to be in his thirties: slim, of medium height, with a scraggly beard, a receding line of curly black hair, and bags under his eyes. His eyes are brown and unblinking, narrowed with intent. “It’s very important.”

The man sets down his glass, stands up, and regards the men in front of him. Except for the older one, they look a little nervous.

“For two hundred fifty shekels, I will get you to the middle of Jerusalem,” he boasts. “Fifty shekels each.” About fourteen dollars per man.

“Fine,” says the oldest of the five, who appears to be their leader. “What do we do?”

The man looks over his shoulder. “Jamal,” he says. “Get these guys to Jerusalem.”

They climb into a battered white van. The door slides shut and the driver begins working two phones, making arrangements. He drives with his forearms as the van rattles down a potholed access road. He turns to the men in the van: “Give me the money.” They haggle over price, finally agreeing on eleven dollars each. “But you have to pay now,” the driver says. He gives them his phone number and tells them to call once they reach Jerusalem. Apparently he wants satisfied customers.

A short time later the driver pulls over and steps into a tall garage made of corrugated metal. He returns with a ladder, extends it to its full length, and rests it against the top of the wall. He scales the ladder and sits beside it at the top. “Come,” he commands.

The men approach the base of the wall and look up, shifting their burdens from one shoulder to another.

They are classical musicians: a violinist, a violist, a double bass player, and two timpanists. Their felt bags contain sticks for concert timpani. The blue canvas case holds a violin. The rest of their orchestra is on the bus, rolling south toward Jerusalem. In four hours, they are due to play Beethoven’s Fourth Symphony in the Old City, at a French church built during Crusader times. Hundreds are expected to attend. If these five players don’t make it, the orchestra’s leader has warned, they will cancel the concert. It is impossible, after all, to play Beethoven’s Fourth without the timpani.

The musicians gaze to the top of the wall, where loops of razor wire present a dangerous obstacle. With a sweep of his arm, the smuggler brushes the loops of wire aside, like a curtain. The razor wire has already been cut. This is a regular crossing point.

The smuggler pulls a long knotted rope from a plastic bag, loops it around a metal post at the top of the wall, and drops it to the other side.

“Ta’al, ta’al,” he repeats. “Come.”

The violist goes first. He mounts the ladder rapidly, sits atop the wall, pivots his legs, grabs the rope, and slowly slides down. He tries to use the knots as footholds, but they are small and his feet keep slipping off.

A vehicle approaches on the narrow access road. The violist freezes about halfway down the rope.

“Who’s in that truck?” he shouts, craning his neck upward. “Are those soldiers?”

If they are, the violist will be arrested or, possibly, shot. It would not only mean he won’t get to Jerusalem for the Beethoven concert that evening. It could signal the end of everything he has been building for years.

————

For Ramzi, at first, it was like a game. Soldiers came; he threw stones at them; they chased him; he escaped. His favorite place to begin the ritual was a yellow stucco wall at a house on the corner of Al Amari’s main road, about one hundred fifty meters from the four-story stone building and the entrance to the camp. Across the road he could see the white plaster minaret of the camp mosque, where, five times a day, the muezzin made the musical call to prayer. During the chaos of the occupation and the resulting absence of local government, the mosque had become a focal point of community life and a trusted civic institution for the exchange of vital information in the camp. Frequently Al Amari’s news was announced over the loudspeaker on the minaret. Next to the mosque stood Kareem’s grocery, with the overstuffed shelves where the brothers got their half-shekel chocolate biscuits.

On a cold morning in early 1988, the older shabab were smashing big rocks and curbstones into smaller pieces, good for throwing. Ramzi watched them wrap their faces in checkered keffiyehs, to guard their identities from the military surveillance crews and the informants, and to protect themselves from teargas. Others deployed fresh-cut onions to dull the effects of the gas.

Ramzi and the other young boys began crumpling newspapers and stuffing them into tires, the better to get them smoking. From his pocket Ramzi pulled out the slingshot he had made from the laces and tongue of an old shoe. He preferred this for long-distance targets. The boys rotated their arms like baseball pitchers warming up in the bullpen. This way, they wouldn’t get cramps.

Someone lit a match. From the blazing tires, twisting black columns rose above the camp, signaling the start of another day of battle. At the camp entrance, soldiers formed an unbroken line. Often they kept their distance, firing teargas canisters, rubber-coated metal bullets, and, occasionally, live ammunition to disperse the crowds. Today, however, the line began to move forward.

Ramzi wrapped his right hand around a jagged piece of curbstone. He glanced behind him to the long row of cement-block homes, checking his escape route. On the rooftops, laundry flapped from metal wires suspended between posts. Crooked TV antennas poked toward the sky

He wore blue jeans and tennis shoes; his red jacket with the faux-sheepskin collar was flying open. In his left hand Ramzi held a rock nearly half the size of his head. His raised right arm was drawn behind him, his hand clutching the piece of curbstone. Ramzi’s eyes conveyed a mixture of anger, fear, and resolve. His arched eyebrows seemed to say, We are here. His left foot was planted, and he was stepping forward with his right. In one more second, the stone would fly.

In that instant, a photojournalist snapped a picture. It captured a lone boy—one of thousands of the atfal al hijara, or children of the stones—confronting an unseen army.

The stone flew and the chase was on. Ramzi turned and ran hard around the corner, past the stucco wall, down the alley toward the bakery. “Stop!,” a voice called in accented Arabic just behind him. Elated and terrified, Ramzi zigzagged through the camp, darting left, doubling back through a darkened passage, bursting into a neighbor’s house, climbing through an upstairs window, and racing along the rooftops.

Still, he hadn’t shaken his pursuer, who ran along below, pointing and shouting.

Ramzi felt his sneakers grabbing the dimples of the tin roof; he saw his limbs pumping in a perfect rhythm with his panting breath. In times like these, in full flight from the soldiers, a strange sense of calm often settled over him. There wasn’t time to put words to a prayer, but he put out the energy of a fragmented offering: God, I love you. I need you. I need to be alive. There was nothing more in the world that could help him; once, a bullet whizzed past, and he understood his life in terms of centimeters. Oddly, in these moments, Ramzi felt protected: buoyed, lifted, and cared for as he ran and ran, sprinting from rooftop to rooftop, leaping toward an imagined freedom.

Click here to read the next excerpt from Grace Notes…

The latest book from acclaimed journalist Sandy Tolan, Children of the Stone chronicles the journey of Ramzi Hussein Aburedwan—from stone thrower to music student to school founder—and shows how through his love of music he created something lasting and beautiful in a land torn by violence and war.