Read all of the excerpts from the second week of Grace Notes.

To promote the release of Sandy Tolan’s latest book, Children of the Stone, Ramallah Café presents Grace Notes, short excerpts curated by the author himself. The book, about one Palestinian’s dream to build a music school in the middle of a military occupation, was released on April 7. Children of the Stone is already receiving wide praise from historians, early reviewers, and the famed musician Yo-Yo Ma. More here.

————

One day, between the curfews, Ramzi took Rami out to explore the open lands on the other side of the hill they knew as Jabal al-Tawil. The hill had been taken over by the Israelis, and from Al Amari, the brothers could look up at red roofs of the settlement of Psagot.

Ramzi led his little brother toward a white brick wall at the northern edge of the camp. They ran through a vacant field and alongside a latticed vineyard. There they veered right, stealing in among the vines. They walked the rows beneath the lattices, laughing and stuffing grapes in their mouths, picking up handfuls of the rotted, fallen fruit and throwing them at each other. Their faces smeared with juice, they ran out of the vineyard with as many bunches as they could carry. They came to the white brick wall, stuffed the grapes in their pants, hoisted themselves to the top, jumped down, and trotted across the Jerusalem road.

On the other side, the boys walked north toward Jabal al-Tawil and the base of the hill, beneath the Israeli settlement. There they encountered a wide swath of high, deep green grass. A foul smell wafted out; they looked up, just east, to see raw sewage trickling down the hillside from the settlement. The boys ran on, into the valley below the hill. They found themselves in a wild land, quiet and uncluttered, covered in olive, sage, and Flora Palaestina. There in the tall grass, on the sloping land, they spotted rabbits, hedgehogs, even a gazelle—wildlife unlike anything they knew at the refugee camp, where the only animals worthy of mention were cats, dogs, sheep, chickens, and the occasional donkey.

At the far end of the valley they came upon a cave. The boys stood at the entrance, squinting in. They moved on, scrambling halfway up another hill, looking back toward Jabal al-Tawil and the valley in between. “Heyyy!” Ramzi yelled across the valley. “Heyyy!” Rami followed. Heyyy! Heyyy! their voices echoed back.

This was the closest the brothers had come to a kind of Palestinian wilderness, a mythical place between the villages of old Palestine, with their houses made of ancient stone. In that place of their collective imagination, the landscape stretched forward, without walls or fences. Without boundaries.

Ramzi and Rami played there for a while, then turned back, walked beneath the settlement, crossed the road to Jerusalem, and went home.

————

One day Soraida saw Ramzi returning from his newspaper rounds. The few remaining papers fanned out under his skinny arms. She greeted him and pressed a coin into his hand. Though their backgrounds were different, Soraida saw them as joined in struggle. The Palestinian uprising was uniting people across religions, class, and gender toward a common purpose: a free and independent Palestine. Soraida was convinced of this outcome. For Ramzi it was simpler: He just wanted the soldiers and the settlers out of his homeland. He wanted to be able to climb Jabal al-Tawil, look out from a summit cleared of machine guns, barbwire, and settlement housing, and see a unified Palestine. He wanted to take Rami with him, so their voices could carry into the valley, all the way to the cave where they had played on that day of exploration.

Soraida wanted to understand the experience of children on the front lines in the refugee camps. She invited Ramzi to lunch in her modest home of Jerusalem stone at 4 Al Ma’amoon Street, where she lived alone. Deep reds of Palestinian embroidery covered the couches and end tables. Books lined the shelves. Over plates of stuffed chicken, rice, and Arabic salads, Soraida explored their common experience. The secret classes she held in her family’s ancestral village of Kobar—about the Nakba and the birth of Palestinian resistance—were much like the lessons Ramzi took in the musty shack in Al Amari. With Birzeit University ordered closed, Soraida had time to work for the nationalist cause. She took village children into the hills, where she taught them patriotic songs and quizzed them about different species of trees. Her village stories were a lot like Sido’s, except that unlike Na’ani, Kobar still existed. Soraida told Ramzi that, much like in Al Amari, the intifada and the curfews had led to high unemployment in Kobar; to generate income for village women, she helped them jar pickles and make fig and apple jams for the local markets. This would be difficult in Al Amari camp, where there were only a few scattered mulberry and fig trees. Her stories intensified Ramzi’s longing to see a real Palestinian village; he had only heard of them.

Soraida was taken by Ramzi’s politeness and his table manners. She tried to draw him out: Does your family worry about you? How many martyrs have you had in the camp? What about you, Ramzi—are you ever afraid? Ramzi was not accustomed to speaking his mind to older people. He was surprised that any grown-up would seek his opinion. Yet Soraida, just one year older than his mother, seemed genuinely curious. Ramzi told her about Aunt Widad’s clandestine work for the resistance, about Aunt Nawal’s polio; about watching Nahil fall on the main street of the camp; about his secret mission to bring food from the produce market. Soraida saw Ramzi as a hero of the uprising. Unlike Sido, she did not spend a lot of time worrying about him. She believed that liberty was coming; this meant that everyone gave everything they had to the struggle. In this she felt a common purpose with the ten-year-old boy at her dining room table.

Ramzi returned Soraida’s invitation, in the tradition of Arab hospitality, and soon she paid a visit to Al Amari. Over tea, Sido and Jamila reminisced about Na’ani. Soraida noticed how their eyes glimmered when they shared the memories of their village. She had spent many hours talking with old people who had lost their land in the Nakba, and though it was sad, she found it helped them to relax. It reminded them that they hadn’t always been in a refugee camp; that they had had a good life, once upon a time. They had all been landowners; it was there, in their villages, that they felt like themselves, even if it was only through their memories.

Before the Nakba, an educated Arab class fueled a vibrant cultural life in Jerusalem, Jaffa, Haifa, and other cities; but Palestine had been a fundamentally rural place. It was at the village level that traditions among Palestinians had been lived and celebrated. In the struggle to maintain a national memory and evoke the dream of return, it was the displaced villagers whose stories were most often retold. Soraida believed it was good for the old people to remind the younger generation who they were, and where they had come from.

***

Soraida and Mohammad knocked on the door of Sido’s house in Al Amari. Jamila, in her Palestinian house dress and loose white scarf, answered and invited them in. Ramzi wasn’t home, but Sido was. The house was spotless, Soraida noticed, and smelled of chlorine, as if it had just been cleaned.

Soraida introduced Mohammad as he looked around the room. A framed greeting in English, made of embroidered beads, read GOD BLESS OUR HOME. Alongside that was a depiction of Al Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem, in yellow, blue, red, and green sequins. In the center of the wall was the poster of eight-year-old Ramzi, holding the pieces of curbstone, under a slogan in Basque: AGORA INTIFADA. Intifada now. Near that, Soraida noticed, was a small framed photograph of Ramzi’s father, Hussein.

They chatted about the village of Na’ani, the end of the uprising, Oslo, the music school founded by Queen Noor of Jordan, the new conservatory in Ramallah, and Ramzi’s plans. He was still in high school, but only for another year. At school, Ramzi was pounding out a five-beat rhythm, Bah-bah-bah-BAH-ba, Bah-bah-bah-BAH-ba, even during class. “Stop it, Ramzi!” the teachers would shout. But it seemed he couldn’t. He carried his humming and rhythms home; Ramzi, his family had concluded long ago, was in his own world, and this was just another expression of it.

Soraida hadn’t noticed any intrinsic musical talent in Ramzi; rather, she believed that as a child from a refugee camp, Ramzi should have the same opportunity to play music as any other child.

Sido told his visitors that he was sure his grandson would be interested in learning music.

“All right, then,” Mohammad said. “Of course we will teach him. Please have him come tomorrow afternoon.”

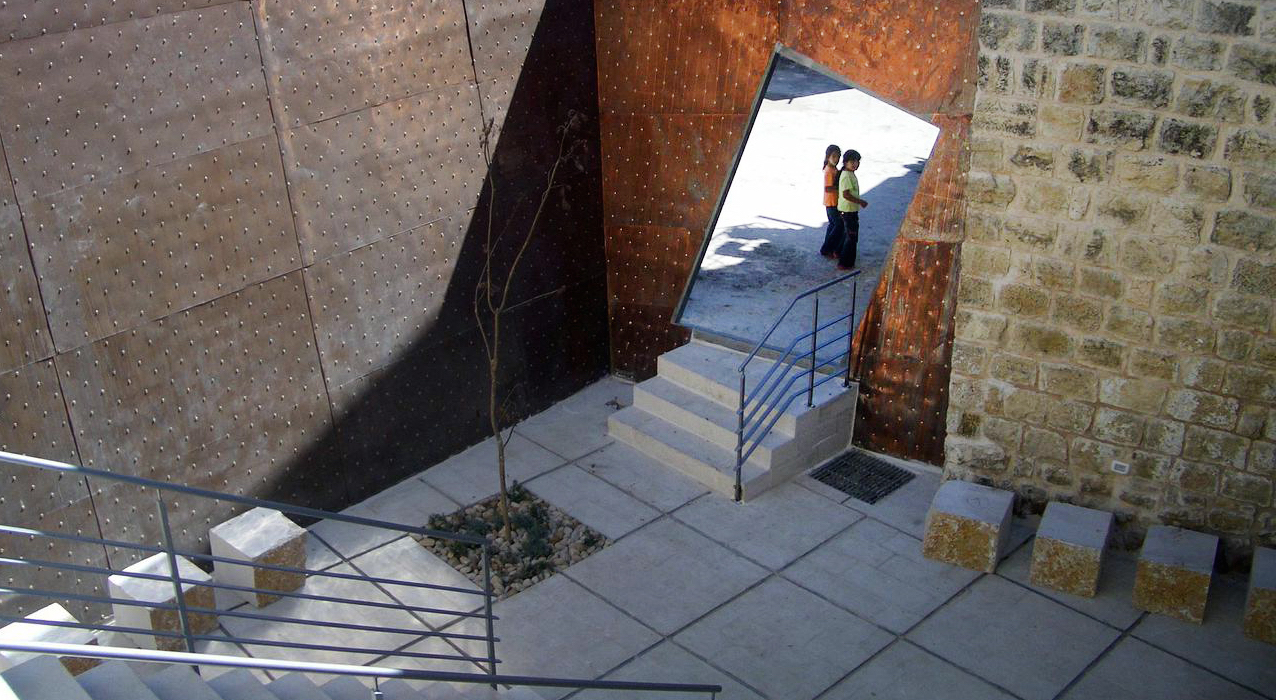

Ramzi climbed the stairs of the new center for music, a short walk from Al Amari camp. When he walked through the door, a few students were sitting in a semicircle as Mohammad Fadel showed them their instruments. Ramzi saw a girl with a cello and a tall, rangy young man with a large bass. On his long face he wore a scruffy goatee and a sad smile. “I’m Ramadan,” he said.

“I’m Ramzi.”

Mohammad came over and introduced himself. “I met your grandfather yesterday.”

“He told me,” Ramzi said.

“What would you like to learn to play?” Mohammad asked, leading him to a room filled with stringed instruments.

“I like the violin,” Ramzi replied, remembering Teacher Khalidi.

“You have large hands,” said Mohammad. “Here, take this one. It’s just like a large violin. It’s called a viola.”

————

Click here to read the next excerpt from Grace Notes…

The latest book from acclaimed journalist Sandy Tolan, Children of the Stone chronicles the journey of Ramzi Hussein Aburedwan—from stone thrower to music student to school founder—and shows how through his love of music he created something lasting and beautiful in a land torn by violence and war.